How the Streamers Can Survive The FTC’s New “Click to Cancel” Rule

The Most Important Story of the Week for 5-Nov-2024

(Welcome to the “Most Important Story of the Week”, my bi-weekly strategy column analyzing the most important (but often not buzziest) news story of the last two weeks. I’m the Entertainment Strategy Guy, a former streaming executive who now analyzes business strategy in the entertainment industry. Please subscribe.)

Judging by my inbox, there’s an election today? And that will likely be a big news story, so let’s remind everyone of my editorial policy:

I write about the strategy of the entertainment industry.

Politics, then, is not my bailiwick, unless it directly impacts the entertainment business, like mergers & acquisitions policy, which I’ve written a lot about recently. (And rightly so, since it really impacts this business. Who can merge with whom does matter!)

In contrast, regulation is often a neglected component of entertainment strategy. As I’ve written before, business leaders who can gauge the future of regulations stand to benefit. For example, Netflix realized that by going over the top, a foreign company could stream video around the world, something many countries prohibited for broadcast and cable channels.

The story of the week is a big regulatory change out of the FTC that could unleash a major change to the landscape of subscriptions, the business model of every streamer. So that’s the topic of the day. All that plus Netflix’s shift in video game strategy, who won the Wuthering Heights negotiation, Disney’s latest theme park price increases, and why I love the Disney Channel Original Movies business model

Most Important Story of the Week - FTC Passes a National “Click to Cancel” Rule

The FTC’s new “Click to Cancel” rule fascinates me, as it touches on everything from consumer preferences to value creation/capture to business models to the role of regulators in the economy to potentially major strategic implications for the streamers. Fun!

For those who don’t know, here’s how

describes it:[It’s] what in the industry is called “The Negative Option Rule.” It’s actually really simple, and just says that it should be as easy to cancel a subscription as it was to sign up for it. There are some additional elements, like firms have to tell consumers they are subscribing to something, no deception on important information, and customers have to agree to pay before corporations can bill them.

How will that impact the streamers? Greatly. But what should they do in response? That’s the topic for today.

But let’s start with the “why” behind this rule.

To Start, Businesses Love Subscriptions (and Consumers Don’t)

If you can remember half-a-decade back, around 2018-2019, the media loved the “subscription economy”. This amused me at the time, because a lot of the folks pushing this narrative stood to benefit from more subscription revenues.

For example, one book (Subscribed: Why the Subscription Model Will Be Your Company's Future - and What to Do About It by Tien Tzuo) extolled the virtues of subscriptions for businesses and customers. At the time—reminder circa 2018—I wondered: wouldn’t an author who’s also the CEO of a subscription software company (Zuora) be a pinch biased? Nevertheless, I saw headlines touting subscriptions as the future all over the place, and at the time, everyone in media seemed bought in.

Then came MoviePass, the ultimate value-adding subscription business, because it just lost tons of money. As the most high-profile “subscription”, think pieces abounded that subscriptions would come to devour the entire economy.

Again, economically-oriented, self-interest-believing little old me was always a pinch skeptical that companies would push altruistic business models just to help consumers. I mean, wouldn’t they stand to profit from subscription models? At least a bit? Or else why do it?

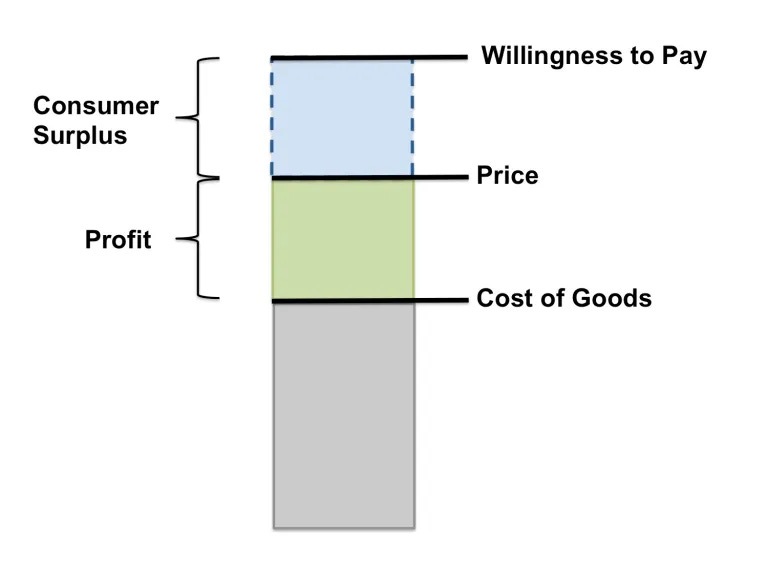

At the time, I wrote a mini-series on this to elaborate on how effective subscriptions were at capturing value from customers. As a reminder, this is the classic “value creation” model for a one-time purchase:

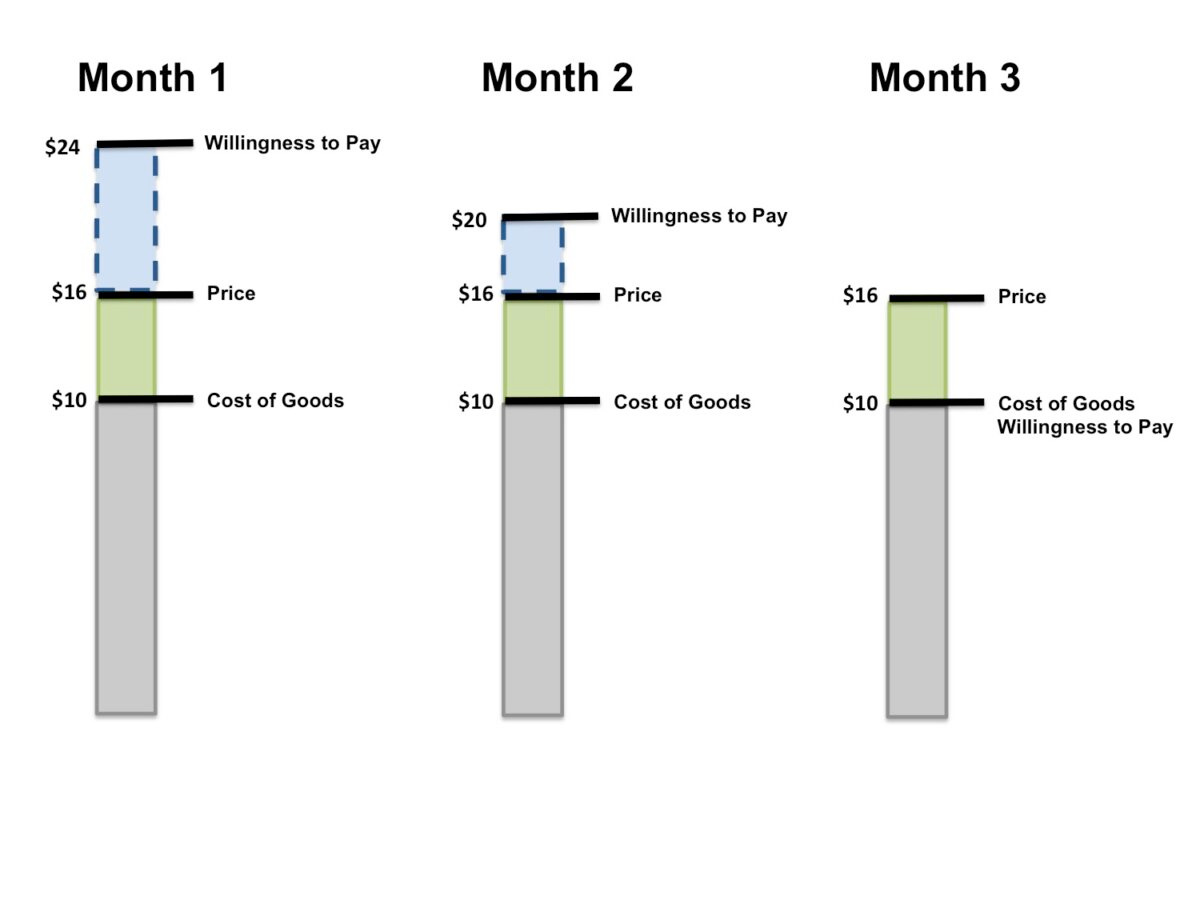

The key thing about a subscription is that, often, they stop delivering value over time, and the “willingness to pay” shrinks over time, but the price does not. Here’s a quick example I made in 2018:

It’s a feature, not a bug, that many subscriptions exist to get customers to pay even when they no longer value the subscription. And you can see why they might put up roadblocks in months three or four to make it even harder to cancel.

Half-a-decade or so later, the subscription model no longer holds the appeal (at least to consumers) that it once did. Derek Thompson summarized it well with the pithy headline, “The End of the Millennial Lifestyle Subsidy”. In sum, most of the deficit finance/zero interest rate business models that benefitted consumers at the end of the 2010s have disappeared. Most of the huge consumer surpluses of the late 2010s were, in fact, illusory, and many of them were subscription-based. Take Netflix, which started life as an $8 streamer (with unlimited password sharing) and now costs $28 for the top tier membership (and no password sharing). Indeed, I called this out about MoviePass at the time. If you actually used MoviePass enough to benefit, they lost money. If you didn’t, then they benefitted. MoviePass just made the biz model explicit (with a dash of “we’ll have customer data” magic sprinkled on top.)

That’s why hearing/reading interviews extolling the benefits of subscriptions for consumers felt so…off. If you rank the most hated industries for consumers (think cellular phones, health insurance, cable companies), they often have subscription business models. Customers kinda hate subscriptions because, again, they often rip them off.

And using Occam’s Razor…that’s probably why businesses love them?

This gets to the rule of the day. Making it hard to cancel, or just wildly inconvenient, means a company can capture more value from consumers. Customers pay for goods or services they don’t even use. That’s all value capture for the business. Again, customers hate this.

I think journalists/pundits/analysts should use the terms “value capture” and “value creation” more in their coverage. It matters when a firm is creating value by offering a truly innovative product (like Netflix) or lowering costs with innovative cost reductions (like early Walmart) versus simply capturing more value, leveraging either financial engineering (think Big Banks circa 2019) or market power (like later Walmart).

Subscription business models, junk fees, bundling, and price discrimination are usually value-capturing, not value-creating, changes.

Remember: Buying Decisions Are Simple; Product Design Is Not

Since attending business school many moons ago, one place I’ve updated my economic priors is the role of “pricing” for consumers. It influences buying more than I previously realized.

Ostensibly, a customer balances two things in their head…

The price of a good

The “quality” of the product, good or service, meaning how well it delivers on its purpose/value for the customer.

Quality, in this case, can mean lots of things. A product can deliver unique features, or deliver its value better than its competitors, or it can be more reliable/durable, or the company could have the best customer service. Or it can be low-quality, but still good quality for the low price. In this sense, “quality” can mean lots of things. For subscriptions, this can be even more complicated.

In the past, I would have treated “price” and “quality” roughly equally. Nowadays, I give price more weight. The problem is that price is often relatively simple (a dollar amount), but “quality” encapsulates dozens, maybe hundreds of factors. If a customer assumes two goods are roughly the same, and one is drastically cheaper, they’ll go with the cheaper option.1

That leaves an opening for companies. Since a product or good can have dozens of attributes, they can tweak the less visibly important ones in their favor. For example, the ability to fix or repair your iPhone isn’t the reason anyone buys a smartphone. So Apple can ban customers from fixing their own property, and they won’t lose any sales. In fact, they might sell more phones! (If the phone breaks, and you can’t fix it, you may buy a new one.) But for customers, that’s a huge blow to the quality of the product they didn’t consider.

This is where smart regulation can come in. Consumers buy or use a product for one ostensible reason, but can dislike a lot about the product, but have little to no choice to switch.

Take the cable bundle. For decades, consumers had few other easy options to watch TV than cable. As such, most customers HATED it when the volume of commercials rose during commercial breaks. But advertisers/cable companies insisted on this habit of turning up the volume during commercial breaks. Again, no one would “cancel cable” over this annoying, yet minor, product choice.

So what were customers to do? Lobby regulators. Congress passed the CALM Act, and that law had one of the highest approval rates in government history. Again, this unlocks a lot of value for customers—no more annoying loud commercials—but likely had little impact on ad buyers or sellers. Customer value for the win! (Cable companies did immediately try to break the rule, and legislation has been introduced to apply the rule to streaming…)

A number of beloved, obvious regulations fit this mold:

Customers love being able to switch cell phones and keep their phone numbers. (Cellular providers hated it and lobbied hard against it.)

Customers would love to transfer all their automatic bill payments to a new bank. (Banks are fighting this right now.)

Customers hate fees getting tacked on at the end of online payments. (Ticketmaster is fighting this FTC rule right now.)

Customers want the right to fix broken technology with the cheapest provider while keeping their warranty, not relying on the company itself. (Apple, in particular, hates this rule.)

Customers hate it when they buy digital goods and then later lose access to them. (I wrote about this last issue!)

I could go on.

The point is that the FTC or Congress can pass simple rules that unlock huge value for customers. Yes, that often means it comes at the expense of some business profit. But as most examples above indicate—especially in less competitive markets2—the benefits to customers can often well exceed the costs for companies.